Multum in parvo

a Eulogy for Ellen Cortner

Delivered in the Jones Meeting Room of the Johnson City Public Library,

May 11, 2009, by her son David and daughter-in-law Amy. Check back for photos and for a more elegant presentation by and by.

[DAVID:]

I can't tell you how good it is to see so many people from so many facets

of my mother's and my lives. Many of us have been too perfect strangers,

and perhaps we will take this opportunity to make new beginnings. Others

of you I have only heard about in stories I could never keep quite straight.

What I get crooked today, I'd love for you to set straight later.

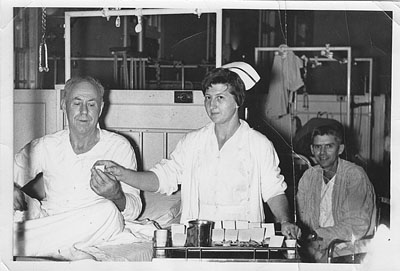

[Unscripted paragraph, walking along a table of artifacts:]

What

we have here… pins from nurses training, as much of a nursing uniform as

I could find (she gave most of hers away), a handful of watches she managed

to wear out taking pulses, a sphygmomanometer (a blood pressure cuff to

you and me), and a pair of scissors she bought during nurses training and

managed to use for over 50 years (whenever she'd leave them out on the

ward or in a patient's room, other nurses knew to return them to a particular

desk drawer where she'd retrieve them) are the barest physical shorthand

for a long life committed to a few, deeply-felt ideals and many enthusiasms.

In amongst the commemorative pins were these sinkers for fishing.

She used to love fishing. I

found a pin commemorating her first 200-game with her bowling league.

I'd forgotten how much time we spent bowling and how much

she enjoyed her seasons in the leagues at Holiday Lanes.

I found this box, it's gold-embossed, "Fine

Jewelry" and

wondered what I'd find inside: it held a cheap, plastic UT key chain

that at one time played "Rocky

Top." Ellen's ashes are in a simple cardboard box inside this train

case. I wanted to set the box out here in plain view — it looks like

any other box ready to be mailed. The frugality would suit her, but

Amy thought that would be a little too in-your-face. She suggested we

use the train case. I told her I thought that was a little too kitchy and

easy — a too-obvious metaphor for "moving on" and all that. So

we compromised. We did it Amy's way.

The arrangement of tables here is purposeful. It's like a big bridge game, a game my mother loved almost as much as she loved poker. In the center of all the tables are tablets or scoresheets and pens or pencils. I'm not asking you to keep score, but if you think of something you'd like to leave with us, jot it down. After I finish these remarks, you're welcome to share yours, or just leave them behind. In either case, I'll appreciate every one. There are also a couple of copies of her obituary on each table.

What I thought I would do is get my copy of the obituary and go through it with you. It is short. I didn't know it actually cost a buck thirty-six per line to insert a notice in the newspaper, and if I had known that, Mom would have wanted me to keep it even shorter. No matter the length of any obituary, a fuller, more satisfying truth lies between the lines, unwritten, and not so much in the exact phrases as in the reasons for choosing those phrases. So this is a little like Mark Twain's "The War Prayer." I'm going to ask Amy to read the published obituary with you, and I'll explain another, fuller text that lies hidden within it.

I'll apologize up front in case this gets a little intense. I looked for a tag I could wear that said, "Hi, I'm David. I can't make eye contact today." Couldn't find one. It's nothing personal.

[Amy reads the boldfaced text of the printed obituary, my remarks follow:]

Mrs. Ellen Cortner, 83, died Thursday, May 7, at the Johnson City Medical Center Hospital following a brief illness. She died painlessly and peacefully, having spent her last hours in the company of her son and many friends.

I want to tell you, in case any of you are troubled by any doubt, that hers was the easiest exit from this world it is possible to have. To those of you who were praying for my mother, please believe that that is the way in which your prayers were answered. She had the opportunity to review her wishes with me. Her doctors and nurses were without exception cooperative, helpful, and solicitous in following my instructions to ensure that she died exactly as she wished. So while you may think your prayers were unanswered, I tell you they were not, and I am very grateful to all of your for them.

She was raised during the Great Depression in Gray, Tennessee, and graduated from Science Hill High School and from the Knoxville College of Business during World War II. Her first job was coloring photographs in Miller's department store in downtown Knoxville; her second was with the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge.

Isn't that a couple of sentences? Most of my mother's formative years were spent on a hardscrabble farm in Gray, Tennessee. She showed me the house in which she, her parents, her sisters and her brother lived. It would have made a pretty good chicken coop, and at one time it probably did. Like many children of the Great Depression, she learned a kind of caution and frugality that could be mistaken for cheapness. If you knew her, you knew the difference: she would spend almost nothing on herself, but think nothing of spending almost anything for others, especially for me. So while it is almost trite to remark on the earnestness of her saving and her attention to finances, it is easy to overlook the other lesson she took from the Great Depression: that we must depend upon one another, and it is our duty to help one another as we are able. That's why there's only part of one uniform over there, and a worn out one at that. When she realized she would at last have to give up nursing, she gave her uniforms away to young nurses just getting started. There's a pair of stainless steel bandage scissors over there, too. She bought them while she was in nurses' training, sixty years ago, and carried them ever since.

My mother and her sister Mary both went to Knoxville where my mother learned office skills — shorthand, bookkeeping, touch typing — at the Knoxville Business College. Her dad sent money for his daughters to live on, and my mother earned a little more by coloring black and white photographs in Miller's department store. She heard that there were a lot of jobs available at a big project in a brand new city being built a little ways out of town. And, being a child of the Depression, she did not believe in letting any job go unpursued.

In Oak Ridge, there were thousands of people, and most of them hadn't a clue what they were working on. My mother, of course, had no idea. They knew it had to do with the War, and that it was a secret, and that it meant their jobs and their liberty to talk and to speculate too much about it. She told me about the muddy streets and wooden sidewalks and about a sense of purpose and efficiency that she always missed and sometimes sought to recreate. There are worse models than the Manhattan Project if your goal is to get things done.

Her stories of the muddy streets and wooden sidewalks stayed with me, and when I read about the Manhattan Project years later, they made a tight connection. What the history books talk about, people did. The words in the books represent the labor and the passions of people as real as my mother.

After the war, she undertook her lifelong career as a Registered Nurse.

OK, let me tell you about that, because to understand my mother it is important to understand why she wanted to be a nurse. See, she really wanted to be an airline stewardess. In those days, 1945 and '46, airlines wanted to hire nurses as stewardesses because flights were long, rough, and people got sick. A lot. My mother wanted to travel; she wanted to move; she wanted to see the world beyond Gray Station, Tennessee, and there was nothing like Pan Am for that. So she got in touch and they said, Yes Ma'am, if you're a nurse, we want to talk to you. So she presented herself to the old Appalachian Hospital in Johnson City, where there was a Training School for Nurses, and said, make me one of those. And three years later, she emerged in a nursing cap and whites, ready to travel. And then Pan Am said, Oh, by the way, there are also height and weight requirements. My Mom was five foot two, maybe five foot three if she held her head just right; she didn't weigh much, either, and both those dimensions were, as I understand it, substantially out of bounds. That was one adventure foreclosed by stature. And so, she'd become a nurse to become a stewardess, and ended up being a nurse to be a nurse. But if she was going to be a nurse, she was going to be a good one.

She graduated from the Appalachian Hospital Training School for Nurses and worked as an RN for over 50 years with the Veteran's Administration at Mountain Home and at Specialty Hospital in Johnson City.

My Mom was Ruth McKee all through lower school and nurses' training, where she was mostly known as "Mac" or "McKee." But her first job in nursing was with the V.A. at Mountain Home and the government insisted on using her first, given name which was Ellen. She married my Dad in 1950, so her name became Ellen Cortner. It could get confusing.

c. 1950-1953.Not long after she started working for Mountain Home, it dawned on her that there were other V.A. Hospitals all over the country, and if Pan Am wasn't going to help her get out of east Tennessee, then the V.A. might. She put in for a transfer. Long Beach, California. That was far enough west. And her sister Mary was already out there (I want to know more about Mary; I met her once, and my Mom went west again years later to care for her during her final illness; but I'd like to know more about her). My Dad's brother Harold was already out west, too. Anyway, my Mom got her transfer to Long Beach, and the U.S. government, bless 'em, gave her three days to get from here to there. This was before interstates, and she didn't want to give Pan Am the time of day, as if mere mortals could afford to fly in those days anyway. Uncle Sam relented and gave her eight or nine days to report for duty, and the drive from here to there in a Buick Roadmaster became a family epic, much of which we retraced piece by piece on multiple trips decades later. That's getting ahead of things. The important thing about my Mom's working for the V.A. in California is that she stayed there not much more than a year.

While she and my Dad — you'll meet him in a minute — were living on Rose Avenue in Long Beach, California, she kept getting letters telling her how bad things were back home. She never talked much about the details. I know she sent money when she could and received a lot of guilt, and it didn't take long for her to understand that she was needed at home to take care of things. I'll never know the details, and that's evidently as she wanted it. If anything in my family was a forbidden topic, it was why, exactly, she felt the need to come home from California. But duty to family came first, and she did. So there was an adventure foreclosed by her sense of duty.

She dealt with whatever situation had brought her back; my dad had a good job back here, too; and between them they could help the family all they needed to. So my Mom felt licensed to try for another adventure.She was still with the V.A., but this time she decided that California wasn't far enough after all. She wanted to go to Korea as a MASH nurse. She and her V.A. connections literally pulled rank and strings to arrange an officer's commission and a posting to Korea. Think of Hot Lips Hoolahan with a good dose of Gaelic temper and a Scottish sense of pragmatism. It would have been mighty. But something stopped that adventure, too. Ellen Cortner was pregnant. In 1955, if you were pregnant, you stayed pregnant, at least for several months. So there was another adventure foreclosed, this time by biology. And, I have to say, by me.

She stayed at Mountain Home as an R.N. for something over 25 years before retiring on disability due to a chemical allergy. If they'd only mopped the floors with something else, she might have stayed on another 25 years. As it is, her friend Elsie Morris's record tenure at Mountain Home was safe. In the late 1970's, she tried actual retirement for a while. Didn't like it. Got a little bored. And that Great Depression thing kicked in again. If you could work and there was money to be made, then you made it. She worked for several years as a home care nurse with one or two agencies. Then she went to work for Specialty Hospital and stayed there for over 15 years until 2003. She especially liked the night shift when the Hospital was hers to run. Her nickname at V.A. was "Sarge," and the doctors and her fellow nurses at Specialty promoted her to "Colonel" or "Major."

In the 1960's, she returned to East Tennessee State College and completed a degree in English with a minor in psychology.

I have no idea how this factoid fits into her biography. Maybe she just wanted to set an example for me. Maybe she just loved words and learning and wanted more of that. I think she was toying wth the idea of going after a medical degree. She talked about that from time to time, but really, by then she just didn't like doctors as a rule and didn't think she could spend that much time bowing down to them. Anyway, there it is: B.S., English, East Tennessee State.

She married Thomas Cortner in 1950 and made a home with him in Johnson City until his death in 1985.

My Dad was not long out of the Navy when he met my Mom. He was a medical technologist at Memorial Hospital while she was, I think, still in the Training School for Nurses. One of her friends who graduated with her, and who spent many of the last hours of her life with her, is here, and maybe Mrs. Kyker, Murphy, can set me straight on these details later.

On my Mom and Dad's first date, they were driving up Roan Street when a car ran a light (or a stop sign) on Unaka Avenue and there was an awful crash. My Mom's face went through the windshield and her leg slammed into the unpadded steel dashboard. She had the scars to show for that forever. I don't know how charming you have to be to launch a girl through your windshield on your first date and still get her to say, "I do," a year later.

My Dad was a farmboy from the Duck River country south of Nashville who saw the world —at least the watery part of it between Hawaii and Japan and between San Diego and Seattle, with the U.S. Navy. He was a gunner's mate assigned to Sky 2 — or maybe "Sky 4" — a 20mm anti-aircraft gun tacked onto the superstructure of a very small ship, the destroyer escort USS Sederstrom, in the middle of a very large and hostile ocean. It was not the kind of place where you wanted to doubt the affections of your Creator. My Dad was raised Church of Christ. The biggest shock of the war for him came not when a kamikaze attacked his small ship off Okinawa, though that made a lasting impression, but early in his blue water career when a shipmate told my Dad that he, the shipmate, was an athiest. Oh, my Dad thought, this ship is bound for the bottom and that right soon. That would be called foreshadowing if this were a novel.

Ellen was the daughter of Margaret Feathers and Stanley Mann McKee whom she adored.

My grandmother Margaret lived with my mother and my dad and me and my mother's youngest sister Phyllis. My mother cared for her mother in our home while she suffered with terminal cancer. My grandmother's influences on my Mom did not, on the whole, lighten her days. Her strongest effects came middle and late and they were a legacy of guilt and suffering. My grandfather's greatest influence came much earlier and his was a legacy of self-sufficiency, unbridled adventure, and unquestioned support.

Stanley Mann McKee left his home in Kansas at the age of eleven. Census records suggest he left home at something more like 14 or 16, but this is the story I always heard. He worked his way north through the Great Plains as a handyman and ranch hand. The railroad brought him south to Erwin where he met my grandmother. They moved to Maryland and then back to Gray. I think my mother was born in Erwin, made that short northward jag, and then returned to the chicken coop in Gray. And then the Depression came. He told stories of his independent life in The West, of winters in North Dakota that sounded like tales from another world. Every day, he walked from Gray Station to the Eastman, where he worked as a machinist, and back in the evening to find his daughter reading her lessons by the light of a kerosene lamp. His stories fed an unquenchable wanderlust in my mother, and his example set the tone of the Depression-era mantra that there is no such thing as "too much work" or a job that was too hard to take on. If there was work to be done, that was a blessing and not a burden.

She was preceded in death by her husband, two sisters, and one

brother. She is survived by one son, David Cortner, and his wife Amy,

presently of Connellys Springs, North Carolina, and by the treasured

members of her bridge club.

The Bridge Club is here in spirit as well as in body. We have intentionally ordered the room as an homage to the joy my mother found in her second family, the ladies of the Thursday Morning Bridge Club. Many visited her during her brief, final illness. More would have done so had they been able or had anyone known the shortness of the time available. Thank you for coming now, and thank you for coming then. Most of all, thank you for enriching my mother's later years. She would want me to remind you that she can still play dummy.

During her long life, she was known in various contexts as Ruth, Mac, Sarge, and Ellen. She was a staunch opponent of the Vietnam War and a proud supporter of labor unions and of many liberal causes.

Let's just say that my mother worked on a military reservation during some of the darkest and most divisive days of the Republic and that she knew what "An Army of One" really meant: it meant that by and large her sensiblities were in direct opposition to almost everyone she knew. It was sometime around the time of Kent State that she told me that if I got a draft notice she would respect my choice: I could either go to Canada or she would shoot me in the foot.

When my mother thought the V.A. was mistreating some of its janitorial and housekeeping staff — they'd report six days a week from places like Mountain City and Rogersville only to be told to go home if there was not enough work for them — she was among the first (if not the first) of the professional staff to join a union in their support. When her supervisor said that she would fire any nurse who joined that union, my mother simply asked if she should pack her bag.

When I was very young, I was pretty sure that I was related to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. I thought he just might be my grandfather. That's because it was sometimes hard to see much difference between the ways my Mom talked about her dad and about FDR. It was very easy to confuse one with the other, and by Occam's Razor I began to believe that just maybe they were the same person. And, of course, you never saw them together. Not until I was old enough to listen to recordings of some of FDR's greatest speeches ("We have nothing to fear but fear itself…" "December 7th, 1941, is a date which will live in infamy…"), speeches my mother heard live over the radio, was I certain that FDR wasn't from around here, and that not only were he and Granddad two different people, but they probably weren't even kin.

There was a big lesson in there: it was possible to find heroes in history books. Actions and words mattered at least as much as blood and examples did. You aren't limited by anything in finding heroes. It was like the time my Dad asked what we'd studied in school and I told him we'd been reading about life on the little island of Makin. And he said, "I've been there." Well, no way, I thought, but he told me all about it. The paths paved with broken coconut shells, three small islands and a cenrtal lagoon, Polynesians gathering breadfruit from the tops of trees, and his ship riding at anchor somewhere in the protection of the reef. And I thought, wow, all those places we read about: they're real. You can actually go there.

That sounds like a big digression, but it's the way it was in my family. You laid out a few big ideas — heroes can live in books; the world is a real place; it matters how you take care of one another — and see how they run together. You don't need to belabor the details. Just keeping those things in mind is enough, if you are kind.

She was a lifelong Democrat (except for one unaccountable vote in 1964) and an avid follower of the Atlanta Braves, Volunteer football, and Lady Vols basketball. She took every opportunity life afforded her to travel.

She just didn't like Lyndon Johnson and voted for Barry Goldwater instead. She thought Lyndon had something to do with JFK's assassination, and she believed things about him that would make Oliver Stone blush. Not for my mother were detailed conspiracy theories and elaborate chains of guilt. She just didn't like the man and was sure he was behind it somehow.

My parents travelled to Florida when the drive was an adventure. More than once, they drove to the Blue Waters Motel in Daytona Beach with their friends Howard and Murph — you met Murph a while back. I was four or five the first time we went to Florida. You had to ride a ferry into Florida because there was no bridge on US 17 then. We stopped somewhere in Georgia and my mom pointed out an odd sign on the side of a gas station. There were three, not two, rest rooms. One said "Men," one said "Women," and one said "Colored." Look at that, she said. Isn't that silly?

With my Dad, my mother and I made an epic loop of the country in 1969 that effectively passed along her father's wanderlust to me.

With one of my school friends, Greg, we went to Florida to see a total eclipse of the Sun. It was cloudy, but it was still a trip, and that was enough to make it worthwhile.

With another school friend, Bill, who wanted to be here today but couldn't get out of a business commitment, we went to Florida to watch the launch of the final mission of Project Apollo. It was a wonderful trip, but when the rocket disappeared into the blue sky, I imagined that my mother mostly felt left behind.

I once drove high into the Northwest Territories of Canada to go kayaking and discovered after all that that the trip just couldn't work. I phoned home, embarassed and disgusted with the way things had turned out, feeling foolish and very much like a cat stuck in a very tall tree. My mother said something vaguely encouraging. But she called back a couple of hours later with an idea. She'd looked into it and wondered why she couldn't fly to Edmonton where I could pick her up in a couple of days and we'd make an adventure of the drive home. Didn't we ever. We saw the northern lights over Lake of the Woods and circled Lake Superior just to see what was there.

With my Aunt Emilie — her late brother John's wife, who's here with us — my mother drove out to Arizona to visit me in graduate school. We went to Mexico, Meteor Crater, the Grand Canyon, Flagstaff, Phoenix, and Tucson. My mom got a speeding ticket "sacking wind" across Texas on the way home. The miracle is that she only got the one.

When my mom bought a small RV about 20 years ago, I thought she would want to try it out on a trip to Roan Mountain or maybe go down to the Smokies. We drove it fifteen thousand five hundred miles round trip to Alaska. It took most of the summer. Along for the ride was one of a series of great cats who were my mother's reliable companions throughout the second half of her life. And if I had done my homework, I could have told her when we accidentally passed about 20 miles from her dad's fabled ranch in North Dakota.

My mother always said she wanted a small place Out West. [Touch train case.] Now she needs a much smaller one. I asked her years ago what she'd like done with her ashes. Oh, she said, you already know that. And I did. Some of them are bound for the most beautiful places she remembers: the Paradise Valley of Montana, where the Yellowstone River passes the Absaroka Mountains; Judith Landing, where the Judith, a small stream named by William Clark, joins the Wild and Scenic section of the upper Missouri; Ninilchik, Alaska, on a particular bluff above the Turnagain Arm of Cook Inlet, where the sky is full of eagles and the horizon rimmed with volcanoes. Use me as an excuse to travel, she said, if you need one.

From an early age, she was afflicted by insomnia, with she often described as a blessing because, she said, it gave her that much more time to read.

There's not a lot to say about that. In the end, what insomnia gave her, macular degeneration took away. I'll donate her magnifiers to the library; we'll find homes for her books.

Her friends and former colleagues are invited to a celebration of Ellen's life to be held at the Jones Meeting Center of the Johnson City Public Library at 11:00 AM on Monday, May 11. In lieu of flowers, Ellen requests that you make a donation to the A.C.L.U., to the Pet Angels Fund at Robinson Animal Hospital, to the Johnson City Public Library, or that you just save your money and maybe buy a good book.

Thank you for coming.

There has been very little talk today of the afterlife, heavenly reunions, salvation, and spirituality.

We didn't talk much about such things in my family. I was introduced to the Presbyterian Church for the first few years of my life and removed from the church when our particular congregation voted not to allow black members. My mother decided then and there that whatever I might gain from church-going would come at far too high a human cost. "Men, Women, and Colored" was an abomination that could stay in Georgia and would find no place in her house. After that, she dropped all pretense. I was raised by an athiest who believed that our duties derived not from God but from reasonable considerations of what makes life better rather than worse for one another.

She believed that death was the end of us, that the end of life was like the extinction of a flame, and that it made precious little sense to think much about what might happen afterward. Probably nothing, she thought, but surely not anything about which we could know enough to argue. At best, she thought she'd find out sooner or later that she was wrong and whatever came after would be a bonus. At this point, some of you should be horrified and some of you delighted by the very same thought: Boy! Is she ever surprised!

Given my upbringing, it's no surprise that the language of spirituality does not come natural to me. But I married a Pre-anethema of Origen, Pre-Second Ecumenical Council of Constantinople Christian, and she can speak it like a native. I don't know exactly what Amy means to say — whoever does? She's as likely to take her text from the book of Whitman as from the Book of Psalms.

[Amy:]

Mrs. Cortner — I called her "Mrs. Cortner" — reminded me of another strong woman whom I greatly admire. She, too, rejected the faith of her fathers and went her own way spiritually. Mrs. Cortner and Emily Dickinson were both russet-haired, physically small women; both adored and were adored by their fathers; and both were denied the roles they craved in the world. Mrs. Cortner found refuge in the world of work, and Emily Dickinson found refuge in the work of words.

I often offer this poem by Emily Dickinson to friends who are bereaved, so it seems especially appropriate now:

This World is not Conclusion.

A Species stands beyond —

Invisible, as Music —

But positive, as Sound —

It beckons, and it baffles —

Philosophy — don't know —

And through a Riddle, at the last —

Sagacity, must go —

To guess it, puzzles scholars —

To gain it, Men have borne

Contempt of Generations

And Crucifixion, shown —

Faith slips — and laughs, and rallies —

Blushes, if any see —

Plucks at a twig of Evidence —

And asks a Vane, the way —

Much Gesture, from the Pulpit —

Strong Hallelujahs roll —

Narcotics cannot still the Tooth

That nibbles at the soul —

[David:]

My mother is finally embarked upon an adventure from which there can be no recall. Celebrate that. The only recall there can be now is recall of another kind: what matters is what we recall of her and what we make of her example. She would have you go in peace and serve the good of one another, according to whatever lights you see.

The title for this presentation was suggested by Dr. Jack Higgs after listening to Amy and me eulogize my mother at the Johnson City Public Library. "What you said about your mother," he said, "puts me in mind of that great quote from Joseph Wood Krutch in writing about Thoreau. Seems to me she was 'multum in parvo,' much in little."

Or, as Amy would have it, quoting Shakespeare by way of "Seabiscuit," "Though she be but little, she is fierce."

obituary | eulogy | last days | more to come